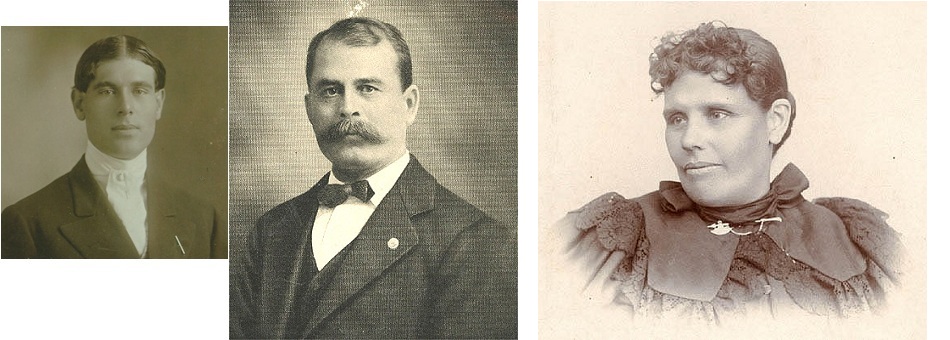

Pedro de la Cruz, alias "Chihuahua"

|

Conspirator, Scapegoat, Victim

I am not the cause

of the uprising!

Pedro de la Cruz

by

Donald T. Garate

Para ti, Pedro: El voz de tu espíritu me habló del polvo, gritando contra las iniquidades tan vergonzosas de los hombres. Cuánto lo siento.

Gabriel Antonio de Vildósola, San Ignacio de Cuquiárachi, September 9, 1754

(AGI, Guadalajara 419, 3m-10, page 22)

The people of my village of Tumacácori fled upon

news that Guevavi had done so, and that those in the

west had already revolted. With this news we left

the village and went to the mountains, or the pass

that leads down to Tres Alamos. The Pimas from

Tubac were also there and those from the rancherías

of Los Ojitos and Piedras Blancas. From there we

separated and some went to join the rebels. I do

not know about anyone revolting because they were

treated badly. Nor have I heard any other cause for

the rebellion. I only know that I fled and went to

the mountain because I saw everyone else doing the

same.

Felipe, Native Governor of

Tumacácori, Santa María Suamca, October 15, 1754

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-12, page 6)

Introduction

Among all the Pimas,

the Caborqueños are the most rowdy, rough, and

unruly.

Bernardo de

Urrea, San Ignacio, November 2, 1754

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-13, page 30)

The story of Pedro Chihuahua must be told. It must

be told for a variety of reasons, the first being

that it has never been done before. Most authors

have barely mentioned his name, if that. If they

have said something about him it has generally not

been complimentary. The book Mission of Sorrows,

referred to him as “a local troublemaker,” an

interesting assessment in light of the fact that

those who knew him categorized him in quite a

different way. A classification of “troublemaker”

can be defended, however, like so much of what is

written as history, but not without extensive

interpretation. The label “troublemaker” by itself

and without a close scrutiny of the person, the

times, and his associates, the cultures, languages,

and emotions of the era and region, may leave the

reader with entirely the wrong impression of the

man.

Indeed, that is what Pedro was -- a man, not a

statistic. He was a person, a living, breathing,

feeling, human being. He was a hero in his own

right -- just as important to the history of the

Southwest, the Pimería Alta, the Valley of the Santa

Cruz, and the story of the Pima uprising as any

governor, viceroy, military captain, or Jesuit

priest. During his lifetime he was drawn to a

variety of different cultural, ethnic, family, and

emotional ties. I suppose he listened to all of

them and was attracted to and influenced by some of

them more than others. Like all of us in all ages,

while being pulled by these forces, he made some

decisions that were regrettable. Regardless of how

unfortunate his decisions might have been, however,

the decisions of his contemporaries, made in a state

of panic and hysteria, were far more regrettable.

Indeed, they were deplorable. So, his story must be

told if we are to understand him and his associates

and the motives behind their actions.

We are told that if we do not learn our

history we are doomed to repeat it. The history of

the Pima uprising is incomplete and cannot be

understood or learned without an understanding of

Pedro Chihuahua and the events he was caught up in.

The injustices and inhumane treatment that were

committed against his person, the prejudices,

hatreds, and biases of his day, and the physical,

mental, spiritual, and economic oppression of one

person, or group of persons, over another person, or

group of persons, in the eighteenth century Pimería

Alta may seem remote, indeed. However, if we do not

learn from Pedro’s experience, and all others like

it, we surely are destined to see it repeated. And,

in reality, we see Pedro’s story played out daily in

communities across America and throughout the world

-- a rather sad barometric reading of how well we

have learned our history. So, Pedro’s story must be

told to help us have the courage to take a stand

against oppression, injustice, prejudice, and

inhuman deeds wherever we contact them, and help

ourselves and others overcome the fears that feed

all such struggles.

Lastly, the story of Pedro Chihuahua must be

studied and understood by those of us who interpret

the history of the Pimería Alta. To leave his story

out of that history would be as unforgivable as

excluding Kino and his associates. While it is true

that Father Kino and those who followed him

accomplished great and far-reaching things, they

could have done nothing had Pedro and his associates

not been there for them to interact with. One group

is every bit as heroic as the other -- and heroic

they were, all of them. It seems highly

inappropriate to me to examine one twenty-four-hour

period of organized riot and killing against a

backdrop of over three hundred years of recorded

history and say these people did not get along with

each other. They got along remarkably well

considering the vast differences of culture and

language which confronted them -- obstacles that

have caused far greater conflicts between other

groups than was experienced here. The Pima uprising

was a tiny blight on the peaceful history of two

peoples who got along so well that their

intermarriages created a whole new race called

Mexican.

We do a great injustice to the people of that

era when we say the Pimas rebelled because of

continued Spanish oppression. Some Spaniards were

oppressive but the vast majority were not. We do a

great disservice when we jump on a bandwagon, either

for or against the government officials of the day,

the Jesuits, the church, or the military. They all

had their tyrants but, again, the vast majority were

common people trying to do the best they could with

the knowledge and abilities they had. And

certainly, interpreting the uprising as though Pimas

everywhere were involved in the conspiracy and the

wanton killings that followed is a grave injustice

to one of the most gentle and peaceful races of

people on the face of the earth. It was a small

(and I believe, very small) percentage of the Pimas

who were involved in either the conspiracy or the

killings. These people, however, whether Spaniard or

Pima, ladino or puro Indio, criollo or gachupín,

priest or parishioner, soldier or politician, miner

or rancher, employer or hired help, were all

individuals. We can never understand or properly

interpret their history as a community without an

understanding of their individual lives.

This, then, is an attempt to interpret one of

those individual stories -- that of Pedro

Chihuahua. However, Pedro could not be understood

without an understanding of his interactions with

his neighbors. So, to that extent, it is also an

interpretation of their individual stories, as well,

as they relate to Pedro Chihuahua. It is not a

complete story of the Pima uprising. For the most

part the story takes place in the trying days just

after the insurrection when literally everyone was

in a state of panic. But, since Pedro’s activities

at that time are so intimately intertwined with the

events of those days, in that sense it is also an

interpretation of the uprising itself.

The story is pieced together mainly from

microfilm at Tumacácori National Historical Park of

documents housed in the Archivo General de las

Indias in Sevilla, Spain. Translations of those

documents that are included herein are the author’s

own. Ed Bledsoe, who was well into his eighties and

who volunteered at Tumacácori translating various

old Spanish documents, unfortunately never got to

these. Although he had translated a few of the

hundreds of documents relative to the Pima uprising

they were all statements of high ranking government

officials and Jesuit superiors. He would have so

enjoyed translating these but, sadly, that was not

to be and we are all sorry for that.

These are all direct translations of the

original documents and the source for each one is

given should anyone desire to read the material in

the original Spanish. The letters are translated

just as they were written in 1751. The personal

testimonies given by Pedro and various other

contemporaries have been changed to read in the

first person, rather than in the third person as the

court recorder transcribed them. This does not

change the information in any way but gives a more

personal feel to their statements and, I believe, a

more intimate understanding of the person who was

speaking. An understanding of real people from

another generation and an enthusiasm for imparting

their dynamic stories to others will bring those

people and their emotions to life for those who seek

our help in understanding the history of the

missions and the Pimería Alta. That is the standard

by which we should gauge our own ability to

effectively interpret that history. Do we truly

know and understand the people of that era and are

we able to inspire others with their essential,

vibrant, spellbinding stories?

It has been said that when asked if she

understood Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity,

his wife answered, “No, but I understand Albert

Einstein!” What a lady she must have been and how

much more important it is to understand the man than

his theories. How much more important it is to

understand the individual Jesuit priest than to have

a full comprehension of the policies he lived by.

How much more important to understand the person who

was governor of Sonora than to have memorized the

Spanish canon law that directed him. And how much

more infinitely important it is to understand Pedro

Chihuahua than the statistics of the time. Although

all of the above is important, we sometimes tend to

forget the real people. And we must never do that.

We must never forget the people. History is an

empty and meaningless shell without them.

The uprising began in the villages to the west from

where it passed to these of the north. Of these,

the first to riot was the village of Tubac, where

they intended to kill Juan de Figueroa. News of the

insurrection passed from Tubac to San Xavier del Bac

where I was governor and where the natives of the

mission were stirred up mainly by the man who was

captain at that time and another Indian who is now

imprisoned at Tubac for being an hechicero (witch

doctor). These conspired and agitated to kill

Father Francisco Pauer but the people did not do it

because of my pleas and supplications. I quickly

informed the Father of the danger, asking him to

avoid disaster by fleeing the village. The father

promptly left with two other Spaniards on horses I

provided. I went with him six or seven leagues and

when I felt he was safe I returned to my village.

There the people were burning the Father’s house and

the church, or ramada, where Mass was said. It had

not been furnished up to now. They were also doing

other mischief with the pack animals and cattle of

the mission and they killed some sheep which the

Father had given me. After committing these crimes

most of the people went to join up with the other

rebels. However, my band and I, along with some

others, although we left the village and fled to the

mountain, we never joined the rebels.

Cristóbal,

Governor of San Xavier, October 19, 1754

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-12, page 23)

The Uprising, Sunday, November 21, 1751

The villages in

which the hostilities, burnings, and killings were

committed are Sáric, where Captain General Luis is a

native, Tubutama, Santa Teresa, Oquitoa, Átil,

Pitiquito, Caborca, Bisani, San Miguel de Sonoitac,

Busani, Aquimuri,

Arizona,

and Arivaca. In these villages, as well as the

Realito de Oquitoa, a few more than one hundred

persons of both sexes and all ages are counted

dead. Among these the said Comisario Cristóbal

Yañes, Romero, and Nava perished. The Reverend

Fathers Tomás Tello and Enrique Ruhen, missionaries

of Caborca and San Miguel de Sonoitac, also died.

All of these fatalities took place on the twentieth

and twenty-first of last month.

Santos Antonio de

Otero, San Ignacio, December 10, 1751

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-36, pages 29-30)

Word first reached the outside world that the

western Pimas had revolted on the afternoon of

November 21, 1751. It was a Sunday and morning Mass

was long since over. At Guevavi, Juan Figueroa,

Father Garrucho’s mayordomo (or foreman) at the

Church’s Tubac Ranchería burst on the scene, bruised

and battered and out of breath. To the north, at

the visita of Arivaca, the Pimas had attacked that

morning at daybreak, killing Spaniards of all ages.

Juan María Romero, the mayordomo there, had been

killed along with his young wife and two small

children. Rumor rapidly spread that farther down

the valley, missions and Spanish settlements were on

fire and under siege. It seemed that the Pimas and

their kin, the Papagos of the west, had joined

forces. In the panic which quickly struck the

community in and around Guevavi it appeared certain

that an alliance had even been formed with the

Apaches. The Pimería Alta was destined for violent

and immediate destruction.

Figueroa, himself, had been constructing an ox

yoke that morning at Tubac, as the few Spanish

residents of Tubac watched and visited with him.

Several natives had been watching him also when, to

his surprise they suddenly jumped him, war clubs in

hand in an attempt to kill him. He managed to

escape, but not without a number of wounds. As he

emerged from the scuffle he could see that the

village was in complete turmoil with people shouting

and scurrying everywhere. Since the majority of the

populace of Tubac were Pimas and since his

assailants were still after him, the only real

choice he had was to flee for the brush like all of

his paisanos were doing. Once he lost his pursuers

he probably assumed that anyone else who had been

there and was not a Pima was dead, so he struck out

for Guevavi.

Even though there were no details as to what

had really happened in the morning, the news that

Figueroa bore struck fear into the hearts of

everyone at the Mission that afternoon. The Pima

natives, some or all of whom might have heard

whisperings of rebellion in the weeks past, fled to

the mountains in fear of what they felt would be

certain retaliation by the Spanish soldiers.

Spanish settlers who had stayed on after Mass that

morning sent runners quickly galloping south to warn

the settlements in the

Far to the south in the Spanish settlement of

Santa Ana the first news of the uprising also

arrived that afternoon, probably about the same time

that it reached Guevavi. There, at least there was

a small volunteer militia, housed by Francisco Pérez

Serrano. But there, also, was the knowledge of just

how vulnerable the frontier really was. The

presidial captains at Terrenate and Janos were in

the process of exchanging jobs. Santiago Ruíz de

Ael had been appointed to take the place of José

Diaz del Carpio at Janos, Chihuahua, and

vice-versa. Ruíz de Ael was on his way to Janos,

several days out with over half of the soldiers from

Terrenate. Diaz del Carpio was waiting for him

there, in the province of Chihuahua, many days

travel from the scene of the uprising. Governor

Diego Ortiz Parrilla was also several days ride away

with the soldiers of San Miguel de Horcasitas.

Captain Juan Tomás de Beldarrain and the presidial

soldiers of Sinaloa were thought to be even farther

away. Unbeknownst to Pérez Serrano, Beldarrain and a

detachment of his soldiers were actually at

Horcasitas. Deputy Justicia Mayor and longtime

resident of the Pimería Alta, Bernardo de Urrea, was

far south at Opodepe, between Cucurpe and Horcasitas.

As Deputy Justicia Mayor, he was in command of the

militia troops of the Pimería Alta.

When three exhausted, dusty and scratched

boys, one of whom was wounded, showed up at

Francisco’s door that afternoon, he immediately sat

down and scribbled out a couple of letters. The

first was addressed to his militia commander, Deputy

Justicia Mayor Urrea at Opodepe. It was carried by

militia Alférez (or Second Lieutenant) José Ignacio

Salazar. The Alférez was dispatched so quickly that

sometime after he got out of town, he realized that

he should have more information than he was

carrying. So, he quickly returned to the village

and questioned the wounded boy, adding his own post

script to Pérez Serrano’s letter. The original

letter reads as follows:

Lord Captain Don Bernardo de Urrea

My Dear Sir

Three young boys have arrived at this place,

one of them wounded, giving notice that the Pimas

have struck in the realito of Oquitoa. These three

escaped without waiting to see more than the fight

that was taking place between the Pimas and the

residents of that realito. I pass this news on to

Your Excellency in this brief form so that it can be

promptly communicated to the Governor. All the

residents and I remain here with the necessary

caution required by such news and, God willing, it

will be convenient for Your Honor to communicate

with me.

In the meantime, I pray to God to keep Your Honor

many years.

Santa Ana, November 21, 1751

P.S. I have returned to ask the eldest of the

said boys (which is the one who is wounded) at what

time the Indians struck in the said realito. He

said it was this morning just as the first rays of

the sun were breaking over the horizon. When he

went through Átil this morning he could see a large

cloud of smoke billowing over Tubutama where he

assumed they had burned the church. I go there now

with the few residents of this place.

Lord Captain, Your devoted servant kisses the hand

of Your Honor

Joseph Ignacio Salazar.

Francisco Pérez Serrano to Bernardo Urrea

Post script added by Alférez

Miliciano Joseph Ignacio Salazar,

Santa Ana,

November 21, 1751

(AGI, Guadalajara

419, 3m-14, pages 4-5)

It appears from this that the decision was made at this point to let someone else carry the letter to Deputy Justicia Mayor Urrea, while Salazar was dispatched with whatever militiamen could be mustered to execute a relief campaign to the settlements in the west. Here, too, at Santa Ana, fear had gripped the hearts of the residents. Pérez Serrano, a fairly old man by this time, was to stay behind to organize the village’s defenses for the imminent attack that was expected sometime that night or by the next morning. He dispatched another runner with a plea for prayers from the missionary at the Mission of San Ignacio, several miles up river. Father Gaspar Stiger was not only the missionary to the Pimas of the area, he was the village priest for Santa Ana. He received Pérez Serrano’s note early that evening:

Word has arrived that

the Pimas struck in Oquitoa and that they killed

most of the people. In Tubutama they killed the

Reverend Father Visitor. In the morning they are

expected to come here, for which I ask Your

Reverence to commend us to God. I will send prompt

notice to Terrenate today. The residents here have

left for Oquitoa because there are only women and a

few men left there with little means of defending

themselves.

May God favor us with his infinite mercy and

goodness and may he keep Your Reverence many years.

Santa Ana, November 21, 1751.

Most Reverend Father, your humble servant kisses the

feet of Your Reverence.

Francisco Pérez Serrano

Francisco Pérez Serrano to Gaspar Stiger,

Santa Ana, November 21, 1751

(AGI Guadalajara

419, 3m-14, pages 5-6 )

It was already evident that rumor, brought about by

the uncertainty and fear of the situation, would be

the driving force behind much of what was done in

the next few days and weeks. The Father Visitor was

not killed at Tubutama. He was not even there. The

two priests who were, Fathers Sedelmayr and Nentvig,

were under siege at the time of this letter, but

were not killed. In fact, there were fewer people

killed at Tubutama than almost any of the other

settlements. Joachín Gonzales de Barrientos, who

was married to Juana Romero, a native of the

Far more people had been killed that same day

and the evening before in other areas. Sáric lost

twenty-two of its residents, eleven of whom were

burned to death in Luis Oacpicagigua’s house. The

realito, (or mining camp) of Oquitoa, evidently

located somewhere northwest of Átil, lost nineteen.

The next worst killing ground was at Arivaca where

thirteen people died. Eleven more died at the

missions of Caborca and Busani. The mission

settlements of Oquitoa and Pitiquito each lost

seven, and six people were killed at Agua Caliente.

Baboquiburi lost five that were known and a few

more. There were three killed at Átil, two at the

Mission of San Miguel de Sonoita, and Antonio

Rivera’s carpenter, Antonio Marcial Espoicucha was

killed near Santa Teresa.

None of this, however, was known at the time.

Over the next few days numbers and names started to

drift in as the “missing in action” were either

confirmed dead or alive -- usually dead. But, for

the time being, everyone’s worst fear was that their

family members in the west had all perished and that

great masses of rebel Pimas were on their way to

kill them next. That same afternoon of November 21,

after Francisco Pérez Serrano had dispatched the

news to Urrea and Stiger, Salvador Contreras, a

miner at the realito of Oquitoa stumbled into town

with more news. He was followed later that evening

by a distraught soldier from Tubutama. Pérez

Serrano dutifully recorded their information to send

to Urrea, but it had to wait until the next morning

to be sent as there was no one left in Santa Ana who

qualified or could be spared as a courier.

Lord Captain Don Bernardo de Urrea

My Dear Sir

Shortly after having sent news to Your Honor

in my last letter that the Pimas had struck in

Oquitoa, Salvador Contreras arrived at this place.

He had escaped by fleeing (because he was

defenseless). He says that he heard the screams of

the Indians just as it was beginning to get

daylight, and immediately afterwards he saw infinite

hordes of them approaching the village and closing

in on it. Some of them swarmed into the house of

Comisario [Cristóbal] Yañez and others into that of

Don Thadeo Bojorquez. Still others attacked

[Manuel] Amesquita’s house and he assumes they

killed all of them. Salvador ran for his life,

putting as much distance between himself and Oquitoa

as he could. Climbing a hill he could see the smoke

from the houses they had set on fire. He also saw a

billowing smoke over Tubutama that appeared like an

enormous cloud where, he also assumes, they had

burned the church and the house of the Father.

Having spoken to him, I write again to Your

Honor to advise you of what appears to be a general

uprising of the entire Pimería so that Your Honor

might promptly advise the Lord Governor. It is

indeed possible that the said enemies of these

territories might overrun us and the damages may be

great, because we have so few men. We are so very

defenseless, considering the few residents who are

armed, as I said in my previous letter to Your

Honor, sent with the Alférez this afternoon.

May our Lord God protect us and may he keep

Your Honor many years. Santa Ana, in the evening of

November 21, 1751.

Lord Captain, your friend and servant kisses

the hand of Your Honor.

Francisco Pérez

Serrano

Lord Lieutenant [Governor]

After I wrote this, it was not sent because

there was no one to be found who could take it. So,

it has remained here until morning. About two hours

after the sun went down a soldier from Tubutama came

here asking for help. He said they were defending

what they could with the few forces they had there,

but that the Pima enemies had burned the church, the

Father’s house, and everything. The said soldier

came here wounded and said that most of the few

sentinels who were there are wounded. All of the

people of Oquitoa and Arivaca are finished, and

notice has also come that they have killed the

Reverend Father Tómas Tello of Caborca. Because of

this we continue to ask God for his mercy and the

Lord Governor for his aid and protection.

Francisco Pérez Serrano to Bernardo

Urrea, Santa Ana, November 21 and 22, 1751

(AGI, Guadalajara 419,

3m-14, pages 14-16)

By Monday morning, November 22, 1751, there were so

many frantic runners dashing everywhere that it is a

wonder they did not run into each other. Pima

emissaries were warning their people everywhere that

a massive killing had taken place and that the

Spanish soldiers were certain to be hot on their

heels. Now was the time to either join the

rebellion or flee to the mountains. Most everyone

fled to the mountains where some made the decision

to go in search of the rebel leaders to join the

insurrection. The vast majority laid low and stayed

hidden until things cooled off. Refugees continued

to drift into Santa Ana, San Ignacio and Guevavi

with more horror stories. Spanish speaking

messengers continued to be dispatched to and from

these areas as the information-starved populace

strived to get the latest news. Unknown to most

everyone was the fact that many of the rebels had

already fled to the mountains, themselves, in fear

of retaliation for what they had done.

In the north, some of the residents of San

Xavier del Bac burned the ramada that Father Pauer

had been using for a church and did some other

malicious property damage before retreating to the

mountains. Once the Spaniards had abandoned Tubac

and Guevavi there was also some property destruction

that took place there, but soon the former missions

and rancherías were totally abandoned of Spaniard

and Pima alike.

Sometime Monday morning, far to the south at

Opodepe, Bernardo Urrea received Francisco Pérez

Serrano’s frantic note. At eight o’clock that

night, when he received the second dispatch from

Santa Ana, he was already three leagues north of

Opodepe at the head of a small group of vecinos (or

residents) of that valley, on their way to give aid

at San Ignacio. They arrived in Santa Ana at eleven

o’clock the next night, Tuesday, November 23. Urrea

listened to all the stories and did a tally,

estimating that eighty-eight people had been killed,

“not counting Father Ruhen in Sonoita and two other

families there.” He was only about twenty short of

the actual count.

Urrea and his local militia were the first to

arrive on the scene, followed closely by Juan Tomás

de Beldarrain and some of his troops from Sinaloa,

as well as others from the presidio at Horcasitas.

Soon the Governor and more troops from Horcasitas

would arrive and set up his headquarters at San

Ignacio. The newly appointed captain of Fronteras,

Juan Antonio Menocal, would arrive soon after the

Governor, if only to find himself in hot water.

Finally, the captains of Janos and Terrenate, Ruíz

de Ael and Diaz del Carpio, would be the last to

arrive on the scene but only because of the great

distance they traveled from Chihuahua, where they

had both received news of the insurrection. All

arrived primed and ready for war, but to their

surprise, they found only abandoned villages.

Reconnaissance missions were sent out to try to

confront the rebels but no real contact would be

made until after the first of the year. In the

meantime, they buried the bodies.

As the soldiers went about their business,

many people, both Spaniard and Pima, came to San

Ignacio to relate what had happened as they

understood it. Soon the story of the conspiracy

began to emerge. Luis Oacpicagigua of Sáric,

Captain General of the Pima Auxiliaries, had been

the planner and instigator of the uprising. His

sergeant, Pedro de la Cruz, “surnamed Chihuahua,” or

“alias, Chihuahua,” as most of the scribes of the

day wrote it was also involved. There were others,

too, but there seemed to be few complaints or

demands being put forth by the rebels. The

complaints that were put forth seemed weak excuses

for such wanton killings, but in the state of mass

hysteria that the Pimería Alta found itself, they

were believed and magnified with each telling.

Juan María Romero and José de Nava had had a

run-in with some Pimas near Arivaca and Romero and

one of the Pimas had been wounded slightly. As

Governor Ortiz Parrilla searched for the causes of

the uprising, this story became more and more

garbled with each telling. Whatever happened,

however, it was certainly not cause for the mass

killing of innocent women and children.

Pedro Chihuahua and Father Garrucho had had a

disagreement at Guevavi over whether Pedro could

actually be Luis Oacpicagigua’s sergeant and carry

the bastón (or cane) of authority for that office.

In the end, Pedro went away offended, having

relinquished his bastón. Again, this could hardly

be considered a just cause for what was to take

place afterwards. Since there was already a rift

between the Governor and the Fathers, however, the

embellished story as it grew from one telling to

another began to look bad for Father Garrucho. Very

few people who testified had been there at the

time. They just told what they had heard and the

Governor’s secretary, Martín Cayetano Fernandez de

Peralta, considered by many to be an avowed Jesuit

hater, went about collecting hearsay as valid

testimony of what had taken place.

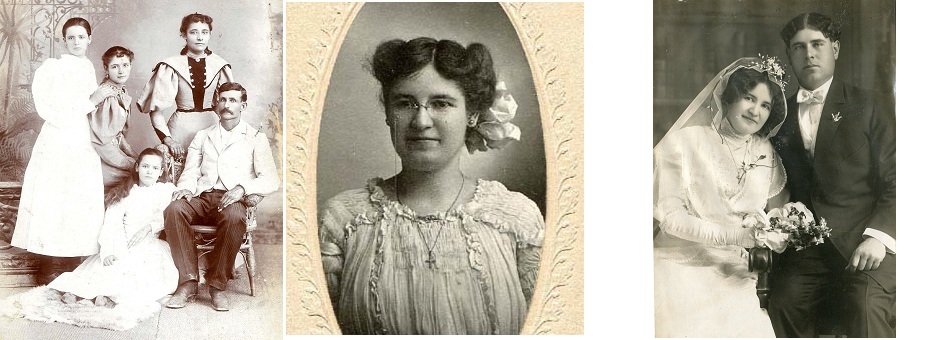

Nicolás Romero, who had raised Pedro from the

time he was nine years old, had been there at the

time. When asked in 1754 if he was aware that

Father Garrucho had taken the bastón away from Pedro

and broken it over his head, Romero said he was

disgusted by the very question, and had been

disgusted by the same question when asked it by

Peralta shortly after the uprising. He gave the

following story:

When the incident

occurred I was at the Mission of Guevavi, where I

had gone for the fiesta of that village. However, I

was not present for everything that happened. I saw

that Pedro de Chihuahua had come to Guevavi in

company with an alcalde of the village of Sáric.

Captain Luis had sent them to Father Garrucho with

some Indians who were from Guevavi but had been

absent from the village quite some time. To make

this delivery, the alcalde of Sáric entered Father

Garrucho’s room with Pedro de Chihuahua, who was

carrying his bastón in his hand. I am not aware of

what took place while they were in the room. There

were other witnesses in the room, however -- not

only Father Juan Nentvig, but I think Father

Francisco Pauer was also there. I did not hear what

Father Garrucho said to Pedro de Chihuahua.

However, I did see that when Pedro left the room and

entered the porch, or ramada, that he came out

without his bastón. The aforementioned alcalde of

Sáric is who was carrying the said bastón. Also, I

and several other vecinos who had come to the fiesta

heard Father Garrucho say to Pedro as they left the

room that he had acted very badly in going about as

a vagabond among the villages. He faulted him for

shirking his responsibilities as a Christian to his

poor wife who had been gravely ill for a long time,

whom he had abandoned in the San Luis Valley, where

she died without him having returned to see her or

care for their children, who would have perished for

want of necessities had it not been for the charity

of Nicolás Romero to succor them.

Statement of Nicolás Romero, Santa María

Suamca, October 13, 1754

(AGI, Guadalajara 419,

3m-11, pages 3l0-31)

The last, and seemingly most important, grievance concerned a confrontation between Luis and Father Keller at Santa María de Suamca. Once again, whatever took place, even if one believes the embellished second and third-hand stories that Peralta was able to drag up, there was hardly cause for the organized riot that took place on November 21. Those stories have Keller calling Luis a “Chichimec Dog” who was not worthy of the title of “Captain General” and who should be out in his loin cloth hunting rabbits like the rest of his kind. Once again, let us examine the testimony of an eye witness, Ignacio Romero:

Luis said, “On a campaign with Captain Don

The Father asked if he had been directed or commanded to do so, to which he responded, “No.”

The Father added that he also knew nothing, and that the captain had left a day and a half before, but that he had taken cattle to feed the Indians who went as auxiliaries from Suamca, and would, thus, not be able to travel very fast. Because of this, if Luis knew the road he could take a short cut and catch the captain in Bavisi or Quiburi.

To this, Luis responded that his people did not come with him to Suamca, but that he had come only in the company of Captain Luis of Pitic and a boy servant of his.

Then the Father charged Luis to pay close attention, and said that if he went on the campaign, the Father did not want him bringing testimony against his neophytes, saying that they were in league with the Apaches like he had falsely done against Captain Caballo before the Lord Examiner, who had ordered Captain Don Francisco Bustamante to interrogate him. That resulted in charges and a sentence being passed against Captain Caballo, for whom Father Keller had testified. The Father told him that he should not be of bad heart, stirring up the Spaniards against the Pimas, or the Pimas against the soldiers. This was not the way of good captains, nor those that have a good heart. Hearing this, Luis twice lied to Father Keller, saying that it was not so -- he had never done such a thing against Captain Caballo.

Upon hearing this, the Father did not treat him like a dog, or say anything to infuriate him, or disturb him, but with total control, responded: “My son, I have the letters in my possession that were written for you by José Ignacio Salazar to Don Miguel de Urrea wherein everything I have said is written. Nevertheless, I lie and you tell the truth.” Then the father added, “Listen, My Son, if you want to go on the campaign, do not bring testimony against my children, because I will defend them. Look. Do you know this Spaniard that is sitting here (pointing to me)?”

“Yes,” he replied.

“And, do you know,” added the father, “that he understands the Pima language well?”

To this Luis also replied, “Yes.”

Then the Father said, “Well, look. I detained this Spaniard, who came here on business, as a witness, knowing that you would deny what was said here and bring testimony against me like you did Captain Caballo.”

To this, Luis made no reply.

Then the father also accused him of consenting to the many robberies of the Pimas in the west, especially at Sicurisuta, the hacienda of the heirs of Captain Anza. He said that good captains who have good hearts do not consent to such things, and that the Father cannot support him when he says he is Captain General but consents to such acts. He said that he cannot indulge Indians who claim the title of hunter and walk through the mountains and across the valleys killing cattle that belong to another person without even asking. And, in case they are unable to ask the owner, the mountains have deer and rabbits and other animals that they can hunt. They do not have to maintain themselves by stealing.

The Father also made one other accusation in which he said that if Luis wanted to go on the campaign like he was, carrying a leather vest, musket, shoulder belt, sword, and Spanish arms that he did not know how to use, it would just serve more to embarrass him than cause damage to the enemy. The Father further asked how many times he had gone on the campaign being supplied by the Fathers with food, horses, and other equipment and everything necessary for the fight against the Apaches, only to return when the supplies were used up, while spreading falsehoods and accusations against his own people.

Nothing else was done or said by the Father that would hinder his having said everything in front of witnesses and having detained me.

He then also said to Luis, “If your coming here was so that you could go with Captain Don Santiago, traveling in his company, then it is not your duty to command, but his. And likewise with my neophytes, only he should command them. Indeed, both yours and mine should go subject to Spanish arms on all campaigns. However, it is not clear to me who has command in the North of your arms, which are the bow and arrow. Clearly, in the past there was no one to take command, but now I do not know who it is because of the division which you see in your wanting to be in charge of everything.”

This is all of what I heard Padre Keller say to Luis of Sáric. I would add that if this is why Luis was resentful, it was because he was admonished about his faults, or I suspect because they still have his mischievous letters on file, or because during the conversation the Father neither asked him to have a seat or gave him any chocolate as they were accustomed to doing for him in other places. Certainly his resentment was not caused by the Father having said that he was a dog, coyote, or a woman, or anything even similar. Indeed, nothing like that was said. This has always been my declaration to Lord Governor Parrilla during the repeated times his secretary, Peralta, has interrogated me.

Testimony of Ignacio Romero, Santa María de Suamca, October 14, 1754

(AGI, Guadalajara 419, 3m-11, pages 40-43)

The leader of the uprising was Luis of Sáric,

Captain General of everything. I do not know what

his motive was for rebelling. I have heard it said

that he rebelled because Father Keller chastised

him, but I do not believe it. It was said by his

relatives that when Father Keller chastised him he

had already been planning his rebellion. More than

a year before when the corn was still short he had

been going around promoting the uprising. When he

went to see Father Keller and the Father chastised

him, he was only looking for excuses, to see if the

Father would give him any reason to start the

rebellion. News of the insurrection reached Suamca

at night and although some went to join the rebels,

most of the people stayed on at Suamca until Father

Keller went to Terrenate. Those, with their

governors, then went to the mountain where they

stayed without joining the rebels, even though they

were asked to unite with them, until after the

tumult had died down. Then they returned to the

village.

Whatever the cause of the rebellion might have been,

the people everywhere, Spaniard and Pima alike, were

not terribly concerned with it. Their only concern

for the moment was self-preservation, something that

seemed very precarious at the time. Had they had

assurance that they were going to survive the

insurrection, they might have taken into

consideration what the causes and effects were, that

they might have avoided such pitfalls in the

future. In those first days after the uprising,

however, the future looked far too bleak to be

worrying about what might have caused the killing

and destruction.

At the Guevavi Mission and on the ranches

along the

As the little party rode south, the newly

constructed church with its locked door must have

looked forlorn in its abandonment. It would not be

long, however, before it would be visited again --

this time by rebels bent on vandalism. As they rode

away, it would look even more forlorn with its

interior in a shambles and its door left ajar. It

would be several weeks before the church would be

visited by a reconnaissance party of soldiers from

Terrenate. They would take a quick inventory of the

damages while guards kept a watchful eye in all

directions. Then they would ride away and it would

be many months before the forlorn little church

would get its community back. Father Garrucho was

gone forever but Father Pauer would be back to

witness happier days.

In all the years I have lived in this Pimería,

communicating and dealing with virtually every one

of its missionaries, at no time have I ever seen any

of the alleged mistreatments. Nor have the Indians

ever complained of them. Those who have complained

of such grievances after the uprising do so that

they might excuse themselves, in this manner, of the

atrocities they have committed.

Nicolás Romero,

Santa María Suamca, October 13, 1754

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-11, page 33)

Río

I knew [Pedro] very well from the time he was a boy

because he was raised in the

Ignacio Romero,

San Ignacio, February 18, 1752

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-56, page 24)

Under any other circumstances, the people gathered

for Mass on Sunday morning,

As it was they were a big, scared family on a

forced march to Terrenate. There were probably a

couple of hundred people present, but not everyone

was able to attend Mass that morning. Many were

guarding the cattle and horses and pack animals.

Others were on scout duty, watching the passes for

any incoming riders, whether friend or foe. But

whether at Mass or not, all were together

spiritually. Their prayers went up in unison for a

safe delivery to Terrenate. There was also a

supplication in each heart for a lost loved one or

for the safe delivery of a family member whose

whereabouts or condition was unknown. Children

could feel the ominous concern of the adults, and

were not their normal carefree selves. They were

being watched closely by everyone to assure that

none strayed from the main body of people. Everyone

was in a state of mourning for some family member or

friend whom reports had confirmed dead in the west.

They had been traveling three days now from

their homes, and the caravan was to get underway as

soon as Mass was over. Horses had to be saddled,

pack mules had to be loaded, and all had to get into

formation and keep moving in a way that would best

protect everyone. Once saddled up and moving

everyone kept a wary eye out for anyone or anything

approaching from outside the group. Family members

stayed close together and their hired help stayed

close around them. Probably the most vulnerable

were the arrieros (or mule packers) and vaqueros,

who were bringing up the rear. The arrieros had to

keep track of the pack mules with the precious

supplies that kept the refugees alive while

constantly watching over their shoulders for fear of

an attack by the Pima rebels. The vaqueros,

completely in the rear, were driving the spare

horses, beef cattle, sheep, milk cows and goats that

everyone hoped to save from the savagery of the

rebellion -- a task that required constant attention

without the added burden of watching for would-be

attackers. Many of the young men of the group had

been assigned to that task.

All who were vaqueros were not young

Spaniards, however. Old Juan Nuñez, an Opata

Indian, was with the group driving the livestock.

His age and experience probably added a measure of

security for the younger and the more nervous of the

vaqueros. Juan had been around a long time and knew

the country like the back of his hand. If there was

going to be an attack, he would know where it would

come from. He knew where special vigilance was

required and where there was less chance of

problems. He had been a cowboy on the Guevavi

Ranch, employed by the Anza family, ever since

1731. Though employed by the Anzas, the Sosas had

always run the ranch for them, so Juan was close to

them as well. His mulata wife, Rosa Samaniego, was

traveling with the women and children of those

families far ahead in the middle of the caravan.

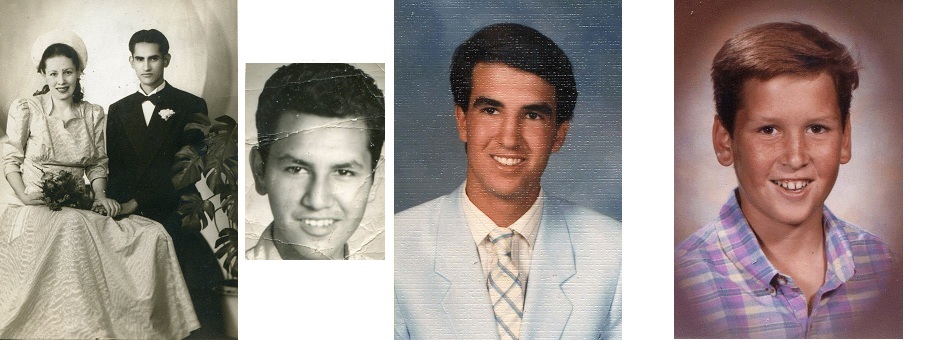

Also helping with the driving of the livestock

was another Indian. He was Pima on his father’s

side and Opata on his mother’s. He had a few horses

of his own running with the rest. His name was

Pedro de la Cruz

Evidently Pedro’s parents must have died,

leaving him an orphan when he was very young,

because he was taken in by Diego Romero and his

family when he was nine years old. What the

connection was between them is also an interesting

question, because the Romeros lived far to the east

on their Santa Barbara Ranch in the

Having been raised among the Spaniards of the

His wife, María Ínes de la Cruz, had died

earlier that fall at the home of Nicolás Romero,

following a lingering illness. Pedro had returned

to the Valley to get his little children upon

receiving news of her death. Now, just some two

weeks ago, Pedro had come home, with his three

children, driving some horses that belonged to him.

He was seemingly fully repentant, and the Romeros,

who were fully forgiving, had welcomed him home with

open arms. He had moved into the house adjoining

Nicolás and Higinia’s home in which their hired man,

José de Vera and his family also lived. Working

side by side with Vera and the Romeros, he had been

living in their full confidence for eight days when

the insurrection erupted in the

As the caravan moved slowly eastward

messengers continued to gallop back and forth

between villages, carrying the latest news, and with

it, the latest rumors. There was no way that Pedro,

thinking himself safely hidden from the forces in

his native culture who wanted his participation in

the uprising, could have known about the forces that

were building against him in his adopted culture.

Only yesterday, Saturday, November 27, a condemning

letter had been carried from Father Stiger at San

Ignacio to Father Keller, who had gone to Terrenate

for safety from his mission at Santa María Suamca.

The same basic letter had gone to Father Visitor

Felipe Segesser at Horcasitas. Since Father Stiger

was closer to the front lines of the rebellion than

either of them, both Keller and Segesser would

assume that he knew the details which he outlined.

Little could they have known that his condemnation

of Pedro as one of the instigators of the uprising

was based on pure assumption and the hysteria of the

moment. Regardless of the accuracy or inaccuracy of

its contents, the letter went out and was duly

received. The wheels of fate that would seal

Pedro’s doom had started to roll forward:

My Beloved Father Visitor, Felipe Segesser:

I am sure Your Reverence has already learned

from other sources of the uprising in this Pimería,

but I will give you the details of its condition.

On Sunday the twenty-first of this month at sunrise,

the Pimas struck at the house and

The rebels burned Caborca at the same time and

killed the Father and those who were with him, as

well as others who were in the mines and mining

camps. At the same time they killed a lot of people

in Oquitoa, Sáric, Arivaca, Tubac, etc., and burned

whatever churches there were. Father Enrique and

his mayordomo and a servant are all dead, and thus

is the account of everyone. All of the Papagos have

joined with Luis. I convened a general meeting on

Sunday night on instruction from a servant of the

Father Visitor. I called one of my officials at

night and told him not to frighten these people, but

to go. He left and with hardship went to the

village. They resolved in their meeting that all

those who could (which amounted to a few criollos of

the village and all of those from Ímuris) should

leave. Casimiro Ureño set out for Ures, notifying

those of Cucurpe and Toape of the uprising. They

have stopped at Toape and are waiting for me but I

am afraid to leave. The insurgents have also stolen

some things from the Yaquis who fled, but the Pimas

have done nothing to the Yaquis and one of them is

with Captain Luis north of Guevavi. All the people

of Santa María have left for good, although some did

return. Those from Cocóspera still remain

peaceful. At San Xavier there were seventeen men

who got the Father out alive.

The political authorities have made various

requests of the Lord Governor, none of which have

been filled yet. I do not know who was sent away

from Terrenate but at Fronteras the people have all

gone. If the Indians should attack here we are in

grave danger of losing everyone. As your life

endures, Your Reverence, will you insist that the

governor send as much help as he can promptly to

take back what we have lost and strike the rebels

with a decisive blow. Right now, the people here

cannot set foot outside of their houses because of

the great fear. And there are very few gente de

razón to defend the Fathers in the north. Indeed,

they already killed Julian near Guevavi, as I wrote

from here yesterday -- Friday. On Saturday,

however, knowledge was gained that those who were

separated from Captain Luis went with their chief to

the mountain called the Cerro del Chile, saying that

the Spaniards were coming to destroy them. The

Spanish captains are in Janos for a time and, thus,

we cannot hope for any help from that quarter. In my

letters I have not asked for anything else from Your

Reverence, or the Father Visitor, or his resources.

By my calculations, eighty-two vecinos have already

died and I do not know what has happened in the

north. I have frankly been working under cover for

Father Salvador (de la Peña). I am committed to

Holy Sacrifice for Your Reverence and ask God to

keep you many years.

San Ignacio,

Gaspar Stiger to Felipe Segesser, San

Ignacio,

Father Keller was at this very moment on his way

back to Suamca. He was traveling in the presence of

Alférez José Moraga who had been dispatched from

Fronteras with seven soldiers to see to the Father’s

safety. Also with the party was Alférez Antonio

Olguin of the Terrenate garrison. They all knew

that the Spanish settlers of the

My Reverend Father Gaspar Stiger,

I received Your Reverence’s letter from the

corporal. I am sending a little gun powder that I

acquired in Terrenate. God willing and with care it

will arrive in good condition, for I am told that

the insurgents have assaulted Your Reverence in San

Ignacio. God grant Your Reverence to come off

victorious if they have struck there. I have no one

here in the north to protect me. All have fled and

even though those in Cocóspera are loyal, I have no

desire to prove them.

Terrenate,

If Your Reverence should see the Father

Visitor and Juan, give them my affection.

Ignacio Xavier Keller to Gaspar Stiger,

Terrenate,

Later that afternoon when the little party arrived at Suamca, Father Keller, taking the situation fully in his own hands, sent another letter back to Fronteras with the following plea to its captain:

Lord Captain Don Juan Antonio Menocal

My Dear Sir:

Under pretext of the right of summons and

having been notified by the Reverend Father Gaspar

Stiger, I ask Your Honor to arrest Pedro de la Cruz,

alias Chihuahua, second in command of the uprising

in this Pimería Alta, to proceed against him as

ordinary justice requires to suppress the fires of

the rebellion that have already caused the death of

two fathers and wounded two others. He was party to

all this and a spy for delivering the Padres and the

other two wounded and the rest of the Spanish

families into the violence of the uprising and war.

Under the said pretext Your Honor should use his

military right, granted him by custom of war.

May God keep Your Honor many years. Santa

María,

Your servant and chaplain kisses the hand of

Your Honor.

Ignacio Xavier Keller

Ignacio Xavier Keller to Juan Antonio

Menocal

(AGI, Guadalajara 419, 3m-54, page 54)

That night as the courier sped eastward with Padre

Keller’s request that Pedro be arrested, the

traveling horde of San Luis Valley refugees camped

for the night at a place called Los Fresnos (The Ash

Trees), just a few leagues south of Santa María

Suamca. One of their number, Pedro Chihuahua, had

been accused of being one of the prime movers of the

insurrection and a spy for the rebels. No one in

the entire group knew of the accusation, with the

exception of one man, and he was by far a more

sinister character than poor Pedro. The latter was

on a course of destruction while the former would

soon be elevated to the office of lieutenant in the

Los Fresnos,

God well knows, Sir, that this punishment is

being administered without fault for I know nothing

about what you are asking me.

Pedro de la Cruz,

Santa María Suamca, November 29, 1751

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-56, page 7)

The refugee camp was slow to get moving that

morning. With all the small children needing to be

cared for it hardly could have been otherwise.

Everybody had to be fed breakfast. Once the men in

camp had eaten they had to go relieve the night

guards so they could come in for breakfast. Pots

and utensils had to be cleaned and packed. Just

getting everything loaded onto the pack mules after

breakfast required the help of most everyone and a

fair amount of time. Although life had been

stirring since daylight and the camp was a beehive

of activity, it just took time to get everything

ready for the camp to move out as a unit. But, it

was good that they were busy. It kept their minds

off their sorrows and fears. It was good to have a

purpose at hand to stem the almost overwhelming urge

to panic. Besides, their minds were probably

somewhat dulled as a result of the small amounts of

fitful sleep that everyone had been getting over the

past week. Probably no one took note of the

beautiful, sunny day that had dawned. The pall of

imminent disaster still hung like a dark and ominous

cloud over their heads.

One thing that everyone noticed as the last

minute preparations were being made before mounting

up, was that five soldiers had ridden into camp from

the north. Nearly everyone recognized Antonio

Olguin, the Alférez in command of the group. He was

a local man who had been raised in the vicinity of

Suamca. The prominent leaders of the refugee

families gathered around the soldiers to ascertain

their purpose. There were Nicolás, José and Ignacio

Romero, Gabriel de Vildósola, Antonio Rivera, Miguel

Diaz, Juan Luque, Juan Grijalva, and Luis Pacho,

among others. The two Fathers, Garrucho and Pauer,

also came forward to greet the soldiers. And, there

was another individual there who seemed to keep

coming to the forefront of late, even though no one

seemed to know him well. Those among the group who

knew who he was were not impressed. Yet, here he

was, all but taking charge of the situation.

Francisco Padilla was from

He did not wait around for the rest of people

there to get organized, however. He immediately set

out alone for Terrenate. There he conferred with

Father Keller and it is relatively certain that it

was he who informed the Father that Pedro Chihuahua

was in

In actuality, Padilla was a fugitive from

As with everything else that had been

happening over the past week, there was a sense of

urgency and no time for small talk. Alférez Olguin,

who did not know him personally, asked where he

might find Pedro Chihuahua. Turning to look over

his shoulder, Ignacio Romero pointed him out. He

was by Ignacio’s own campfire, as were both

Ignacio’s and Pedro’s children. To everyone’s

surprise, with the exception of Francisco Padilla,

the soldiers rode over and placed Pedro under

arrest. Clamping him in leg irons, they placed a

rope around his neck and led him out of camp toward

Suamca as swiftly as he could walk with shackles on.

There was no scuffle. There was no protest --

just complete shock and surprise. The children were

quickly reduced to tears. Had they not already had

enough to bear without this? The women, putting

their own grief aside, tried to comfort them. The

men, now spurred into action by this turn of events,

quickly finished the last minute preparations to get

the camp moving. Everyone wanted to know what was

going on. Ignacio Romero was the Deputy Justicia

Mayor for the jurisdiction they were in. If anyone

was to have given an arrest order it should have

been him, but he was in such a state of shock that

he probably never thought to protest this breach of

his authority. Besides, this was war. Even though

he did not know why Pedro had been arrested, he felt

the soldiers had jurisdiction over him in this case,

and he, along with the rest of the camp, quickly

mounted their horses to follow the soldiers and

Pedro Chihuahua into Suamca. Probably no one took

notice that Francisco Padilla mounted up ahead of

everyone else and went with the soldiers.

Antonio Olguin had been under verbal orders

from José Moraga to arrest Pedro de la Cruz, alias

There Pedro was chained to one of the upright

posts of a porch-like ramada attached to Father

Keller’s house.

By that time the entire caravan of people and

livestock from the

Firmly secured to a tree at the edge of the

village, Pedro’s shirt was removed. As the searing

lashes of the whip administered by one of the

soldiers began to fall across Pedro’s back and

shoulders, he screamed in pain. “I had no part in

the rebellion!” he cried. Another crackling snap of

the whip and another blood curdling scream. “I am

not at fault in any way!” he shrieked. Yet another

lash from the whip and a loud moan from the forlorn

figure tied to the tree. “Before God, I am

innocent!” he wailed, blood now dripping from his

back.

Alférez Moraga allowed the whipping to

continue for three or four more lashes before

calling it abruptly to a halt. By now Pedro was

slumped down, barely conscious. It was obvious that

this man was not going to admit to any wrongdoing.

He was untied and taken back to the ramada, shaking,

stumbling, and limping, still firmly secured in leg

irons. There he was once again chained to the

upright beam, but his battered body sank to the

floor.

The burning question on everyone’s mind now

was either, “What would be done with Pedro?” or,

“What could be done with him?” Certainly he had

confessed to nothing. Those who knew and loved him

were wondering why he should be held in such a

manner. Those responsible for his arrest needed

some evidence of his conspiracy to justify their

actions. The next order of the day was to devise a

means to obtain a confession. Pedro’s main concern,

lying miserable and bruised on the hard ramada floor

where he was chained, was survival.

A soldier was left to guard him through the

night, from any attempted escape on his part, or

from anyone in the refugee camp coming to talk to

him. Those in the camp experienced another night of

fitful sleep. Surely, Pedro’s children and possibly

others, cried themselves to sleep. Alférez Olguin

went to look after the spare horses of the caballada

that night. Fathers Garrucho and Keller, Alférez

Moraga, and the two mystery men, Padilla and Aguilar

Montero went into conference at Keller’s table just

inside the door from where Pedro was being held.

The final outcome of that meeting was that Padilla

was commissioned to obtain a confession from Pedro

-- a bizarre turn of events.

I

commanded that he be tied to a post to see if he

would declare that he had influenced or participated

in the rebellion. Having thus far denied it, he was

given six or seven lashes. After he responded with

various exclamations that he was innocent and knew

nothing of what he was being asked, I ordered that

the whipping be stopped.

Joseph Moraga, San

Miguel de Horcasitas, April 22, 1752

(AGI,

Guadalajara 419, 3m-57, pp.9-10)

As day dawned over Mission Santa María de Suamca the

next morning, word soon spread through the refugee

camp that Pedro had confessed during the night. No

one knew to what he had confessed or what his

alleged confession might mean. Probably no one

stopped to wonder about the authenticity of a

confession that had been obtained by a man they

barely knew. This was still not a time for rational

thinking. Rumor continued to be the best form of

information that most people could obtain. Besides,

the respected patriarch of the whole community of

the

As the day progressed, the rumor mill

continued to grind out both information and

misinformation. Most people were too busy with

their continued preparations for the rest of the

journey on to Terrenate, still another fifteen miles

away, to spend much time thinking about what Pedro

might have said. The fact was clear that under the

given circumstances, he might have confessed to

anything. Who could possibly hold out under such

treatment? Furthermore, these people, for the most

part, were very devout Catholics. They loved their

priest and spiritual guide, whether Keller or

Garrucho. They also knew and loved Pedro for the

most part. True, they had been disappointed when he

went off to Sáric following dreams of grandeur.

True, he had been a follower of Luis of Sáric for a

time. They all knew that, and considered it an

unwise decision on his part. But the second in

command of the rebellion -- a conspirator to murder

and mayhem -- that they did not believe.

Now, as Pedro’s confession slowly became

public knowledge, on top of all the fear and

mourning they had already been through, with one or

two days travel still left before they reached their

final destination, were heaped bizarre stories of

things that Fathers Garrucho and Keller had

allegedly said. Suddenly, Francisco Padilla, about

whom there were also plenty of rumors floating

around, was everybody’s savior, including Pedro’s.

It was Garrucho and Keller who had insisted on

Pedro’s beating and Padilla who had argued for

restraint. It was Garrucho and Keller who were

insisting that he was guilty and that he should be

tortured until he confessed, while Padilla had

begged to be able to privately and quietly speak

with Pedro. In that manner he would be able to gain

the prisoner’s confidence and obtain his

declaration.

According to Padilla, it was Father Keller who

came up with the idea of obtaining a confession from

Pedro the way he had seen it done in Germany,

legally and under German law. There, the story

went, they would pass an iron meat hook under one of

the criminal’s ribs and hang him in a tree where “he

would naturally die from grave pain.” It would seem

that under this method, whether the person confessed

or not, he would soon be dead and the problem would

be solved. But, Padilla had argued long and hard

against such extreme measures -- or else he invented

them in his imagination. Could he possibly have

been grinding an axe of resentment against the

Fathers for having excommunicated him? In the end,

he prevailed and Pedro was not given the “meat hook”

treatment.

Yes, Francisco Padilla had saved the day --

and Pedro Chihuahua -- by convincing the Fathers and

José Moraga to hold off until he had an opportunity

to quietly gain the poor Indian’s confidence.

Though reluctant, the others had agreed to give it a

try. That night, after most everyone else was in

bed, Padilla sat quietly talking to the exhausted,

pain-ridden, fear-stricken Pedro. He had befriended

him. He had gained his confidence. And, he did

obtain a confession, of sorts, from Pedro. At

least, that is the way the story was going around on

Tuesday morning. Regardless of what truly happened,

these are the words that Padilla recorded that

night, supposedly as they fell from Pedro’s

trembling lips:

I am not the cause of the rebellion. Those who have

caused it are Fathers Jacobo Sedelmayr, Ignacio

Xavier Keller, and Joseph Garrucho, because of the

severity with which they and their mayordomos treat

the Indians. They have also infuriated and

aggrieved the Captain General of the Nation, Don

Luis. He left his village in the month of September

with many armed Indians to make a campaign against

the Apaches. He was to go in company with the

Captain of Terrenate, Don Santiago Ruiz de Ael, but

when he arrived at Santa María Suamca he was

informed that the said Captain, Don Santiago, had

already left his presidio. The Captain, Don Luis,

then went to see Father Ignacio Keller, minister of

the said village, to wish him good day and to learn

the route he should take in order to most quickly

catch up with the said Captain of Terrenate.

With no more having been said than that, the

Father gave the following response: "You are a dog

to come here and ask me that. You can go wherever

you want, or not go at all. It would be better if

you remained behind. You act like you are trying to

be a Spaniard by the arms you are carrying. You are

not worthy to go about in this manner. You should

be in a breechcloth with bow and arrows like a

Chichemeco, and without a servant (because he had in

his company an Indian Servant).

And so he went away with his companions. This

captain says the Father must have been drunk,

because he drinks a lot. From there he returned to

his village of Sáric, very sad and disconsolate

because of the mistreatment he had received from the

said Father Keller and the disdain with which he was

treated.

Telling me of this occurrence, he said to me,

“Brother, I am possessed with this evil of serving

in this charge that was conferred upon me by the

Father Visitor and confirmed by the Lord Governor in

the name of the King. I accepted it in order to be

Captain General of my nation and because the Fathers

could not now scorn me in any way, since they would

have to do as the King commanded. But because the

Fathers detest us we are already lost. So, don’t

say anything to me now about how we should love the

laws of God. It is better that we should live with

our liberty. Already, I do not want these arms or

this uniform. Now I will betray all the Spaniards.”

In effect, this is what he did. Afterwards I

went to the village of Guevavi on the occasion of

the fiesta that is celebrated in honor of Señor San

Miguel Arcángel. I arrived at the house of Father

Minister, Joseph Garrucho, carrying the bastón

(cane) of the sergeant of Captain Don Luis. So, he

bid me enter his presence where he spoke very

indignantly to me in front of many people, saying

when I was there, “You are a dog because you are

carrying that bastón. Don’t come here disturbing

the people. If it was not for the day that this is,

I would have you given a hundred lashes with a

whipping stick.”

After saying this he snatched the bastón from

my hand and commanded me to leave the village,

saying that if I ever returned or if he even heard

of me setting foot in the village, he would have his

justicia administer a hundred lashes in his

presence.

To this I said, grasping the title which I

carried on my chest, “My Father, I carry this bastón

by virtue of this title of sergeant, granted to me

by the Lord Governor, that I might assist my

brother, Captain Don Luis.”

But he responded even more angrily, saying, “I

do not want to see that title. The Governor cannot

grant titles without license from the Fathers. We

have a cédula from the King concerning that very

thing.”

The Father kept my bastón and I went away very

sadly and afflicted to the village of Sáric and said

to Captain Don Luis, “Brother, I am no longer your

sergeant,” recounting what had happened with Father

Garrucho.

To this the said Captain replied, “I was

possessed of this evil but now I have taken the

demon into my body. Now, if we do not finish our

work we will lose everything.” Then in the presence

of three or four Indians (whose names I do not

remember, except one who was called Cipriano), the

execution of the uprising was discussed in

consultation. The said Captain asserted that one

day the Indians would strike in all places, killing

Fathers Jacobo Sedelmayr, Ignacio Xavier Keller, and

Joseph Garrucho because these were the greatest

offenders. Sometime after this consultation it

happened that Father Jacobo Sedelmayr wrote a letter

to Father Juan Nentvig, minister of Sáric, telling

him that he should punish me and not to allow me

into the village until it could be said that I was

subdued. The reason I was not subdued is because of

the animosity the Fathers had for me because I was

the sergeant of Captain Don Luis, and because I was

so persecuted by them. So because of this and

because the fires of rebellion were getting very

hot, I decided to leave the village and went to live

among the Spaniards.

With this purpose I went to the ranch of Don

Bernardo de Urrea to look for my horses, and then I

returned to get my children with whom I went to Agua

Caliente. Even then I was not safe from the

persecution of the Fathers, because Lieutenant Don

Cristóbal Yañez told me, “You must leave here

because I have a letter from Father Jacobo Sedelmayr

instructing me to give you fifty lashes and banish

you from these parts.”

I then went to the

However, I did not go there, nor did he send

for me to come. And I did not have intention of

going there because I wanted to stay among the

Spaniards -- and this is the truth. Before the time

referred to is when the Indians were rigorously

harassed by the way the Father and the mayordomos

treated them. They had not resolved to rebel until

the said quarrels transpired. They were also

irritated because Juan María Romero, Father Joseph

Garrucho’s mayordomo, and Joseph de Nava seized some

Indians and were taking them to the village of

Arivaca to turn them over to Padre Garrucho to

punish them. One of the Indians, a relative of

Captain Don Luis, seeing that one of those to be

punished was his son, shot an arrow at Juan María

Romero, wounding him in the arm. Although it was

not a serious wound, they lanced the Indian and

turned the others over to Padre Garrucho to punish

them further. And, the Father also chastised them.

All of this I declare: since the Fathers have

not always been friendly, and since he was the only

one who could remedy everything, to tell you the

truth, Sir, I boldly spoke to the aforementioned

Captain and said, “Brother, we must all meet

together and go see the Lord Governor.”

To this he responded, “I have already seen

that the Lord Governor loves us very much, Brother,

and for him I am sorry, but we must say, ‘Sir, we

have had enough!’ because I am outraged.

Pedro de la Cruz Chihuahua, Santa María

Suamca, November 29, 1751

(AGI, Guadalajara 419, Francisco Padilla

Testimony, 3m-55, pages 28-35)

As the contents of Pedro’s declaration became known

on Tuesday, some of it made sense to his friends

from the

Then there were the parts of the confession

that were difficult to believe -- just as difficult

as Padilla’s story that he had saved Pedro from the

clutches of the spiteful, sadistic Fathers. The

vecinos had never known the gruesome Fathers

Garrucho and Keller spoken of by Padilla. Nor had

they known the Pedro Chihuahua that emerged from the

written declaration. Could Pedro really have

carried those kind of grudges against the Fathers?

Not the Pedro they knew. Had he not just been

traveling for the past eight days in the presence of

Father Garrucho? If there had been something amiss

in the two men’s relationship, would not someone

have noticed? In fact, no one had noticed anything

even remotely suspicious about Pedro as they all

traveled in his company, both day and night. And it

was not like these people were not fearful and

suspicious of everything and everybody around them.

Those were the forces that were driving them in

their headlong flight to Terrenate.

But now, they were numb, right down to the

inner depths of their bones. The events of the past

eight days had driven everyone to the brink of

complete mental, physical, and spiritual

exhaustion. Nobody knew what to believe about

anybody or anything, anymore. So, they dug in at

Suamca to await the outcome of Pedro’s destiny

before continuing on over the ridge toward the

Presidio of Terrenate. What else could they have

done? In everyone’s mind this was truly war. The

army was in charge and, at least here, there were

some soldiers without whom the refugees themselves

were still not safe -- or, at least, they assumed

they were not. They did not know that the killing

had stopped a week ago. They did not know that the

Pimas had fled in fear, the same as they were

doing. The only difference was that the Pimas had

arrived at their destinations faster because they

traveled lighter.

The most unfortunate part of the story is that