|

MANY PACHECO FAMILY COAT OF ARMS

WITH ONE COMMON DENOMINATOR.

Escudo de plata, dos

calderos jaquelados de oro y sable. Bordura jaquelada de lo

mismo.

Thanks to;

http://www.vicentepacheco.com/escudo.html and others.

History of the Pacheco Family

Name in Spain.

Open Conflict: Tendilla versus the Letrados

[150] One Mendoza was not willing to

abdicate the role of leader. While the family in Guadalajara accepted the

inevitability of this changing intellectual leadership with a graciousness

verging on indifference, the count of Tendilla in Granada fought against the

trend. Conservative by nature and alienated from his Guadalajara cousins by

property disputes, Tendilla's family loyalties were directed toward the

ancestral reference group rather than to the extended family of his own day.

From Tendilla's point of view, the family's political power, its place in

society, its heroes all were associated with the Trastámara revolution and

with the view of Castilian politics and history laid out by Pedro López de

Ayala. Tendilla's adherence to the family's tradition, even at the expense of

family unity, was reinforced by his two journeys to Renaissance Italy and by

his isolation from the new intellectual centers of Castile. When Tendilla

tried to persuade the consejo real to adopt his policies, however, it was not

just an academic dispute over intellectual issues. For Tendilla, as royal

governor of Spain's largest convert population in a period of political and

religious upheaval, every royal decree held life and death implications.

Tendilla did not realize until too late that in a society that had come to

regard tolerance and moderation as deviance, it was no longer profitable to

maintain the Mendoza family tradition.

Iñigo López de Mendoza, second count of

Tendilla, was the eldest son and namesake of the first count of Tendilla (d.

1479). He was educated in the household of

his paternal grandfather and namesake, the first marquis of Santillana. He

received his political and military [151] apprenticeship in the

households of his father and his uncle, cardinal Mendoza. His father inherited

one of the mayorazgos created by Santillana; but with three sons and two

daughters to provide for, he tried to increase his estate by service to the

king. He was one of the staunchest supporters of Enrique IV and served as the

king's ambassador to Nicholas V in 1454 and to Pius II in 1458. Tendilla, then

sixteen years old, and his younger brother, Diego Hurtado de Mendoza,

accompanied their father to Florence and Mantua on this second embassy. In

1467, the father was rewarded for his services with the title of count of

Tendilla, and he was appointed tutor of the king's daughter, Juana, who was

taken to live in the Mendoza family residence in Buitrago.

After Enrique disavowed Juana's rights to the

throne in 1468, the first Tendilla and his brother, the future cardinal,

appealed to the papacy for a restitution of her rights and publicized this

appeal by nailing copies of it to the doors of the churches in several

important towns. When the appeal failed, the elder Tendilla handed Juana over

to her new tutor, Juan Pacheco, and seems to have

retired from active public life. Young Tendilla and his brother, Diego Hurtado,

then entered the household of their uncle, the cardinal, and formed part of

his entourage during the summer of 1472 when he entertained the papal legate,

Rodrigo Borgia, and arranged Mendoza support for Isabel as heiress of Enrique.

Tendilla and his father stayed out of the early stages of the ensuing

succession war, and they are the only Mendoza not mentioned in Isabel's

statement of gratitude for the family's support in 1475. Apparently the elder

Tendilla remained loyal to Juana, but he also refused to support Juana against

his own family and stayed out of the conflict in order to preserve the

family's unity.

The second Tendilla inherited his father's

title and estates in 1479; and in the next twenty-five years, he more than

compensated for the disadvantages of having withheld early support from the

winning side. He did this through the Mendoza's traditional route to power and

wealth -- outstanding military service in the wars against the Muslims, heavy

investment of his private fortune in the diplomatic and administrative service

of the crown, and a politically and financially profitable second marriage. In

addition, he and Diego Hurtado were favorites of their uncle the cardinal; and

through the cardinal's patronage, Diego Hurtado became bishop of Palencia

(1473), president of the consejo real (1483-1486), and archbishop of Seville

(1485). Diego Hurtado followed in the footsteps of his uncle in more ways than

one: he too fathered illegitimate sons, became cardinal of Santa Sabina, and

resided at the royal court as protector of the family interests. With such

[152] alliances, Tendilla's career was bound to be favored by the Catholic

Monarchs; but Tendilla himself was a man of exceptional political and military

talents and had all the personal characteristics that modern historians

consider typical of the Mendoza at their best -- charm, courage, boundless

pride, lively intelligence, sparkling wit, shrewdness, and prudence. Above

all, Tendilla displayed a flair for cutting the Gordian knot with a wit and

ingenuity that made him a legend even in his own lifetime.

In 1480, Tendilla married

Francisca Pacheco, a daughter of Juan Pacheco,

his father's rival as tutor to the princess Juana. This marriage culminated a

series of moves taken by the Mendoza in 1478-1480 to prevent the destruction

of the Pacheco Family by Isabel in the succession war. By this marriage, the Mendoza

allied themselves with their traditional rivals in order to preserve that

balance of powers within the kingdom typical of the Enriquista political

structure; and Tendilla allied himself with a family already powerful in

Andaluda and active proponents of war against Granada.

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez

Spanish painter, b. at Seville 5 June, 1599

(the certificate of baptism is dated 6 June); d. at Madrid, 7 August, 1660.

His father, Juan Rodriguez, belonged to the Portuguese family of Silva; the

child took the name of his mother, Gerónima Velazquez. He entered the studio

of the aged Herrera, but could not stand his temper, and soon left for the

studio of Francisco Pacheco, whose school at Seville was the most frequented.

Although one of the most tiresome of romanticizing painters, Pacheco was a

cultured mind, appreciative of a genius opposed to his own. As a critic, poet,

and man of the world, Pacheco was the centre of the first literary salon in

the city, and from this society young Velazquez received an education through

contact and conversation with superior men. Before he was twenty he had

married Pacheco's daughter Dona Juana. Two daughters were born to him before

1622, when the young painter decided to seek his fortune at Madrid.

Here, through Canon Fonseca, a friend of his,

who held a post at Court, he was enabled to visit the royal collections at the

Alcazar, Prado, and especially the Escorial, with its matchless collection of

Tintorettos and Titians. This was the sole benefit of his visit, and after

some several months Velazquez returned to Seville. When Philip IV raised the

Sevilian Olivarez to power, Fonseca summoned Velazquez back to Madrid, and he

obtained permission to paint the king's portrait in the court of the riding

school. This portrait, now lost, was an event. Thenceforth Velazquez had the

exclusive right to paint the person of the king. By a patent of 31 October,

1623, he was appointed painter of the chamber, with a salary of twenty ducats

payable out of the appropriation for court surgeons and barbers.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF ESTEPONA

(Costa del Sol)

Its history involved the Phoenicians, the

Romans and the Arabs. The latter, who settled in this region the longest, left

us numerous vestiges of which very few have unfortunately been saved

(fortifications, watch towers, etc.).

In the strictest historical sense, however, we

are obliged to admit that it is not known when the town was founded. This

might well fall within the time of the Phoenician settlements, and there are

considerate grounds to believe that it might have been during the Roman era.

It is therefore assumed that the Estepona of old existed a good deal earlier

than the Arab "Estebbuna" and "Alextebuna".

The town was captured from the Arabs during the

hostilities ordered by King Henry IV of Castilla in the year 1456. It is from

this moment on that the history of Estepona as it is known today began, with

the very same King Henry ordering the reconstruction of the castle at the

request of his intimate friend and advisor, Don Fernández Pacheco, the Marquis

of Villena.

In the absence of the Catholic Kings, during

the reign of Doña Juana La Loca, or "Mad Jane", the village remained under the

jurisdiction of Marbella.

With more than 600 inhabitants, Estepona

obtained its complete and unrestrained independence under King PhiIlip V, "In

perpetuity and for always without end in all manner of civil and criminal

matters of the first instance within the town and its municipal district", as

is recorded literally in the town Charter signed by the King himself in

Seville on the 21 April 1729 and which is kept in the town archives.

From this moment on its development began in

earnest using its own natural resources, the sea (fishing) and the countryside

(crops), until today and the beginning of the tourist phenomenon.

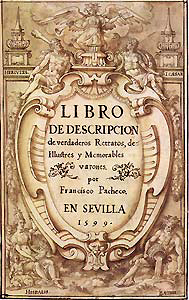

The Writings of Francisco Pacheco

(1564-1644).

'To write history properly has always been

difficult'. With these words Francisco Pacheco, painter and writer in Seville,

described the task of writing an account of the life of the humanist Benito

Arias Montano and, generally, of other eminent personalities of his times.

Francisco Pacheco, otherwise known as the master of Diego Silva y Velázquez,

was a diligent writer. As sometimes happened in seventeenth century Spain,

Pacheco never saw his books printed while he was alive. The Arte de la

pintura (Seville 1649) had no influence until the eighteenth century

onwards, whereas the manuscript-book, Libro de descripción de verdaderos

retratos de ilustres y memorables varones (dated Seville 1599 in the

frontispiece) was quite renowned among scholars and writers of the time, but

never got to the press until the end of the nineteenth century.

My research on Pacheco's writings is focusing

in the Libro de retratos and its relations with the historical and

cultural history of Seville in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Seville was, then, one of the richest and most cosmopolitan cities of Europe,

second only to cities like Naples and Paris. Nevertheless, Pacheco was living

in an in-between age. The dawn of the seventeenth century would usher in the

critical years of Spanish decadence and the loss of control over Europe by the

Spanish empire. Through fifty-six portraits and biographies of eminent

individuals in Spain at the turn of the century, Pacheco acquaints us with the

cultural issues of his age, the social systems and hierarchies, and the

changes brought in by the Counter-Reformation.

The book represents the diverse social ranks

that were to be found in cultivated Spain: a King (Philip II), a town

councillor (venticuatro), poets and writers, soldiers, preachers,

painters, a doctor, a musician, a dancer, a goldsmith. Pacheco shows a dynamic

society that travels to America as well to nearby Africa in search of gold,

convents to Christianity, and mercantile contacts.

Several Spanish contemporaries of Pacheco knew

about the existence of the book, such as the renowned writer Francisco Quevedo

who mentioned the volume in a poem, and the historian and antiquarian Rodrigo

Caro, who reflected in his Varones ilustres. Pacheco was probably aware of

having introduced a new historical genre into his country: half-way between a

chronicle and a collective biography, the Libro de retratos was forgotten

until its facsimile publication by the bibliophile José Maria Asensio at the

end of the nineteenth century. This edition was a success and was followed by

two more in the 1980's.The book is still quoted by Spanish and non-Spanish

historians alike who study personalities of the seventeenth century. Pacheco's

book happens to be one of the handiest primary sources that still mentioned in

essays and biographies. Nevertheless, the text by Pacheco has not been studied

in depth. It still lacks a critical edition and a study of the author.

Information contained in the Libro is cited regardless of his authenticity by

scholars who are content to praise it as mine of data without subjecting it to

any academic analysis.

My PhD is focused in the historical and

biographical contents of the Libro de los retratos. A large part of my

thesis is concerns Pacheco's writing technique, i.e. how did he select the

individuals (eminent and otherwise) and how did he gather the data about them.

From my consultation of sources in Madrid (Biblioteca Nacional, Academia de

Historia, Biblioteca Lázaro Galdiano, Instituto Valencia de Don Juan), Seville

(Biblioteca Capitular y Colombina, Archivo Nacional), London (British Library)

and Oxford (Taylorian). I have identified a large number of Pacheco's sources,

in both manuscript and early printed form. Pacheco's use of them is surprising

to the modern reader; plagiarism is common, but not automatic. The Inquisition

was a lively presence for the author when he was compiling the book: all

allusions to heresy and heterodox views are removed. Nevertheless, I still

need to look into further comparative material and to investigate into

possible patrons of Pacheco's oeuvre and to establish Pacheco's links with the

Church and the Inquisition (Pacheco's brother was, in fact, an inquisitor). I

also wish to look into the historical genres of biographies, chronicles and

histories of Seville. A detailed comparison with the contemporary historian

and friend of Pacheco, Rodrigo Caro is crucial. Finally a comparison with

Pacheco's second book, the Arte de la pintura is essential, and it should also

highlight the differences between Pacheco the painter and Pacheco the writer. Marta Cacho Casal

martacasal@hotmail.com

Belmonte

The province of Cuenca is one of five

provinces within the region of

Castilla-La-Mancha, the other four being Guadalajara,

Toledo,

Albacete and Ciudad Real. The whole area has some of the most historic and

beautiful lands within the whole of Spain. Remains of burial grounds dating

from the Iron Age have been discovered as well as some major Roman settlements

such as those at Saelices and Valeria.

A monumental town of great interest with many,

well preserved architectural gems, not least of all its castle. It was Henri

IV who gave the town to Juan Pacheco, the Marquis of Villena in 1456 .

The castle was erected in the 15th century, on top of a hill in order to

protect the Marquis's domain.

It was built

by Juan Pacheco in 1456-1470 on the site of an

earlier castle dated 1324. It was restored at one point and used as a private

residence. The walled precinct whose 15th-16th century ramparts and gates

connect the old town with the castle is particularly well preserved. Belmonte

has more than its fair share of churches, palaces and convents. The hermitage

of Nuestra Senora de Gracia, dated 17th century is certainly worthy of a

visit.

HISTORY

During the 12th + 13th

centuries, the muslim almohad population of Spain built castles to check

the christian advance. The origins of the castle of the watchtower of Villena

go back to these times. In the middle of the 13th century the

christian troops in the service of games of Aragon twice failed to capture the

castle, until the knight commander of Alcañiz, of the order of Calatrava,

finally conquered the the city of Villena in the name of Jaime I, who then

ceded it to the Castilian King Ferdinand III. The castle passed into the hands

of his last son Don Manuel and from this moments Villena became the head of a

domain which became increasingly important due to its geographical situation

and also to the members of the Castilian royal family who governed in the

city.

On the death of the prince, his son Don

Juan Manuel inherited the fortress which remained the property of the Manueles

until they were incorporated into the crown of castle. The domain of Villena

became a marquisate taking in the lands of Alicante, Albacete, Cuenca, Toledo,

Murcia, Valladolid and Guadalajara. There are no traces of the first marquis,

Don Alfonso of Aragon, in the castle but his successors, Don Juan Pacheco

(first shield), had

the upper part of the homage tower built and his coat of arms appears on one

side of it.

Later, in the time of Ferdinand and Isabella, the people of Villena

rose in

revolt against their marquis, Don Diego López Pacheco and since then the city

and the castle passed into royal control while the title of marquisate became

an honorary one.

The domain of Villena also became a

dukedom, created by Henry III of the castle for the princesses Doña Maria and

Doña Catalina.

The castle played on important role in

the war of the Spanish Succession (1700-1714) serving as a refuge to those

loyal to Philip V of Borbon fighting against Charles of Austria; also, in the

peninsular war, in 1813, Marshal Suchet bombarded the fortress, destroying

same of the almohad domes.

The current state of the fortification

is the result of different initiatives, designed to protect, conserve and make

it better known. The starting point was 1931, the year in which it was

declared a National Historical Monument; later, in 1958, the first restoration

work began. The most recent work dates from the year 2001 and was mainly

focused on the homage tower and the courtyard. Works has already begun an the

restoration of the front section of the wall and further work will be done to restore the whole of the castle.

A LINK TO THE STORY OF

SPAIN THAT INCLUDES THE PACHECO FAMILY.

|